|

Creating Medical Plastics That Heal Themselves

New polymers could allow for self-healing materials, the University of

Pittsburgh recently reported.

Materials manufactured from the new composites can regenerate themselves when

damaged. Results of the Pitt research were recently published in the journal

Nano Letters by the American Chemical Society.

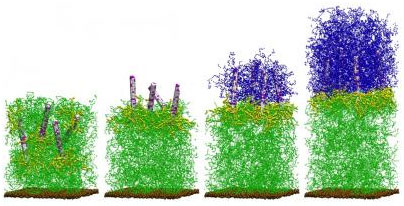

An image of the self-generating composite.

Submitted art: University of Pittsburgh

The researchers drew inspiration from animals that can regenerate missing or

severed limbs. These processes are guided by three unique instruction sets,

described by the study authors as initiation, propagation, and termination.

This threefold process, also known as a dynamic cascade, was replicated by

researchers in a synthetic material. However, developing the self-healing

composite was no easy feat. Because animals and other living organisms can

transport building materials through a circulatory system, it is relatively

simple for an organism to transport the materials it needs to a regeneration

site. However, synthetic materials don’t have such systems.

To create a sensor that initiated and controlled the regeneration process,

researchers created a hybrid material featuring nanorods embedded inside a

polymer gel. This composite is then saturated with a solution contain

cross-linkers and monomers, allowing for a synthetic replica of a biological

cascade.

Because the functionalized chains on nanorods keeps them localized at the

interface, the initiator sites along the surface of a rod can trigger the

desired polymerization process with the crosslinker and monitors in the

solution. Each of the nanorods has a diameter of 10 nanometers.

As the next step, researchers hope to improve the binding between new and older

gels. To make this possible, researchers once again looked to nature. "One

sequoia tree will have a shallow root system, but when they grow in numbers, the

root systems intertwine to provide support and contribute to their tremendous

growth," states Dr. Anna Balazs, principal investigator.

”While others have developed materials that can mend small defects, there is no

published research regarding systems that can regenerate bulk sections of a

severed material. This has a tremendous impact on sustainability because you

could potentially extend the lifetime of a material by giving it the ability to

regrow when damaged.”

A group of European researchers announced research findings on a separate

self-healing material in September.

http://www.qmed.com/news/creating-medical-plastics-heal-themselves

MedTechs Tackle Replacing 'Workhorse' Plasticizer

The jury is still out over whether phthalate plasticizers such as DEHP really

cause health problems in humans, according to Peter M. Galland of Teknor Apex.

But publics and governments in the U.S. and Europe have become convinced enough

that medical device companies will have to find replacements for them anyway. The jury is still out over whether phthalate plasticizers such as DEHP really

cause health problems in humans, according to Peter M. Galland of Teknor Apex.

But publics and governments in the U.S. and Europe have become convinced enough

that medical device companies will have to find replacements for them anyway.

Confronting growing evidence that exposure to phthalate plasticizers could cause

a range of health issues, Congress declared in the Consumer Product Safety

Improvement Act of 2008 that children's toys and items such as pacifiers could

no longer contain di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP), dibutyl phthalate (DBP),

and benzyl butyl phthalate (BBP). At the same time, it provisionally prohibited

three other phthalates: diisononyl phthalate (DINP), diisodecyl phthalate (DIDP),

and di-n-octyl phthalate (DNOP). Then, in December 2012, FDA restricted the use

of both DBP and DEHP in pharmaceutical medicines, citing concerns that these

chemicals are associated with health risks. Clearly, phthalates are not

problem-free.

On Wednesday, February 12, Teknor Apex (Pawtucket, RI) will hold a seminar at

MD&M West on the complex issues involved with replacing phthalate plasticizers

in PVC compounds. Led by Galland, the company’s vinyl division industry manager,

the seminar will concentrate on the use of phthalate and nonphthalate

plasticizers in PVC-based and certain non-PVC-based medical devices.

“Phthalate replacement has become important to medical device manufacturers

primarily because environmentally minded NGOs such as Greenpeace waged a

decades-long, unsuccessful campaign against PVC and a more recent successful

effort against phthalates, the primary family of plasticizers used to soften

PVC,” Galland remarks. However, there is scientifically no compelling human

health reason to replace plasticizers like DEHP, Galland adds. And while

researchers have discovered that ingested phthalates, particularly DEHP, can be

causatively linked to liver tumors in rodents, there is no such link in humans

because humans metabolize DEHP and other phthalates differently.

While FDA thinks that the toxic and carcinogenic effects of DEHP demonstrated in

laboratory animals have not been shown in human studies, it acknowledges that

there are certain invasive medical procedures during which exposure to DEHP

could exceed acceptable levels. Thus, FDA focuses on the small subset of medical

devices in which DEHP-containing PVC may come into contact with the tissue of

sensitive patient populations in a manner and for a period of time that may

raise concerns about the aggregate exposure to DEHP. Many devices used in

neonatal intensive care units, according to the agency, meet this criterion.

Affected medical devices could include IV tubing, catheters and cannulae, and

enteral tubing.

Next

|